By Eugene Healey / 02 September 2019

10 min read

Brands are in a difficult spot right now. Memes, and the internet culture that surrounds them, are akin to a new language that’s fundamentally shaped the way we communicate with one another online. It’s a language that’s complex, rapidly evolving and, for the majority of large corporations, seems to remain impenetrable. Every now and then this cultural myopia results in something so iconically terrible it can’t be ignored, but this masks the broader issue of mediocre content being made with no real understanding of the audience it’s being served to.

It’s time to lift our heads out of the sand. For brands, understanding culture remains essential, because it shows they understand the audiences that participate in that culture. Meme culture in particular requires a challenging rethink of the relationship with that audience: moving away from authoritarian brand management and creating a more permeable platform that others can contribute to and influence. But a big payoff awaits those who are taking the time to become fluent in the language of the internet: being given the rare opportunity to participate in, and even shape the cultural conversation as it unfolds in real time.

Memes, a brief history

The term ‘meme’ was originally coined by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in 1976 to explain how ideas and behaviours spread between individuals within a particular culture. To him, a meme was a single quantifiable unit, something that facilitated a transfer of cultural information through a process of imitation and replication. Dawkins treated ideas as if they were subject to the same process and pressures of evolution that biological entities were: find a suitable host to display a behaviour, have others reproduce it—or else, die out.

The modern, often bizarre world of internet memes may seem abstracted from the original concept but they share the same essential traits. The collection of images and videos we encounter online do more than make us laugh. They can be a vehicle used to drive home a message, either to positive or nefarious ends. Memes can be the shroud of levity that gives us the outlet to publicly express and own our flaws and anxieties. And they can be a way for people to connect with others by discovering that the oddities of their own personal stories are actually shared experiences (in the case of Subtle Asian Traits, the oftentimes strange experience of being a diasporic Asian living in the Anglosphere).

Source: iFunny, Facebook

In essence, internet memes are an important medium through which culture is consumed and shared online. That means, by definition, meme culture is culture. And given that so few brands have a genuine ability to understand meme culture, much less participate in it, they’re missing out on an opportunity to connect deeper with online audiences who are the next legion of consumers.

Fogies, begone

The level of ‘internet illiteracy’ that brands suffer from is especially dire whenever they hop on the bandwagon to coincide with a particular cultural moment. While it’s easier than ever to participate, it’s also much easier to miss mark.

The final season of Game of Thrones was made bearable only through the cacophony of memes created by the fanbase after each episode. They ran the gamut from playful, to absurd, to philosophical, to extremely scathing. In fact, the worse the show got, the better the memes did. By the end I was looking forward to the memes more than the show itself. They made it feel as if I were not merely watching television but participating in some kind of transcendent cultural experience.

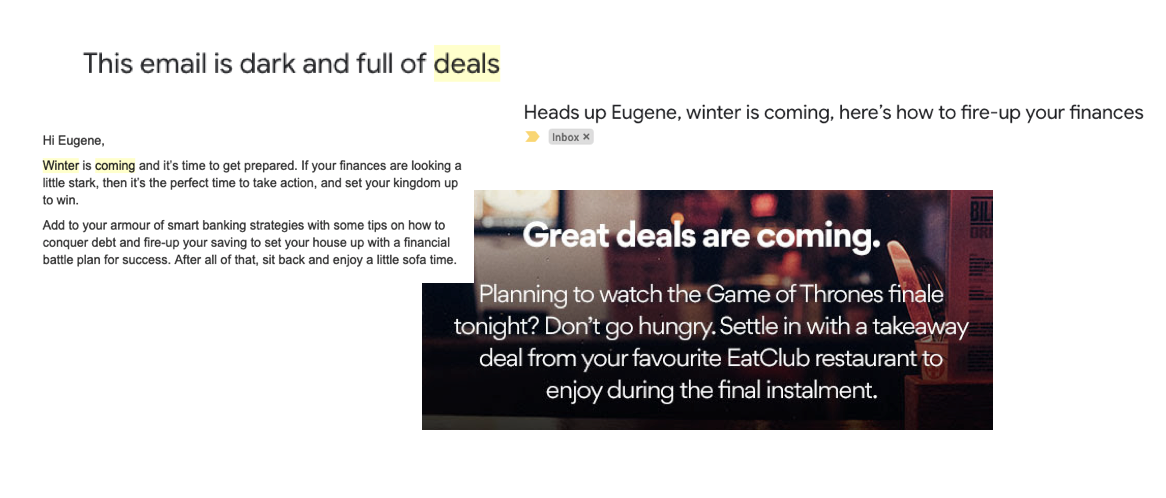

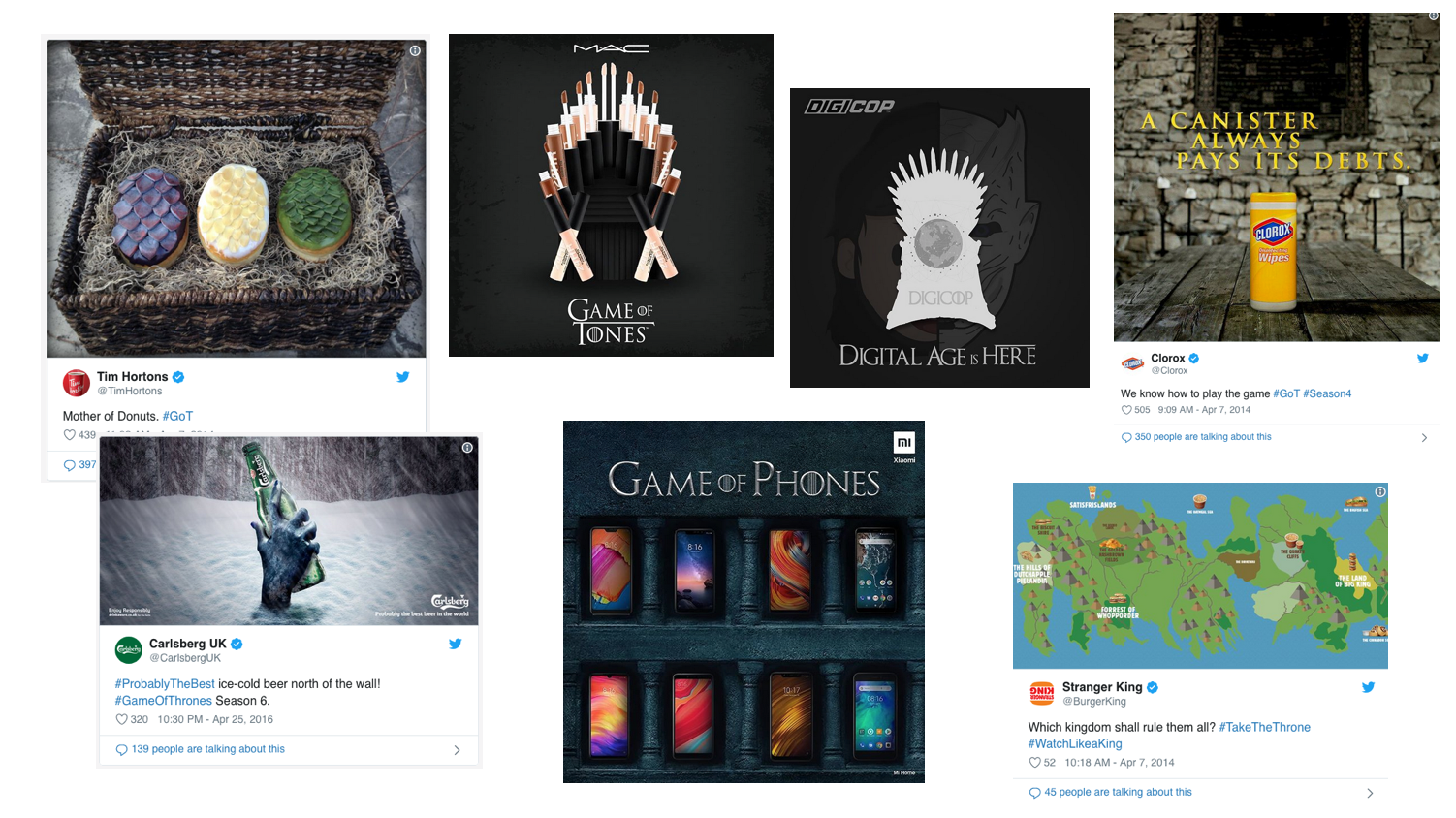

Compare that against the comms I was receiving in my inbox at the time, along with some ‘content’ I’ve found around the web from the past couple years:

This is the brand equivalent of Hillary Clinton dabbing on Ellen. It flags a desire to leech from, not participate in the zeitgeist, lip service paid only as a trojan horse to communicate some banal marketing message. Held up against the things the public makes for free, their entertainment value is left seriously wanting.

Greater opportunities abound for brands who instead take the time to become genuinely fluent in meme culture, because the content they create is calibrated much more closely to the eyeballs of its intended audience.

Consider last year’s excellent Tide Pod Superbowl ad. What was it, if not a meme? It played on the audiences pre-existing understanding of established Superbowl ad genres (in effect, meme templates), inserting itself into each one, mutating and recontextualising them to suit the brand along the way.

You can’t sit with us

I’m not suggesting brands all rush out to enlist their own ‘junior meme copywriters’ to begin churning out their own deluge of branded memes. In fact, this is a plea for the opposite.

Because the truth is that memes lie on the bleeding-edge of a conversation that is in constant and unyielding flux. Most brands are simply not built for that level of cultural agility. Internet communities can instinctively sniff when a corporate message masquerades as an internet meme because the content used is generally already decaying by the time it gets through the approval process.

Source: Struthless

There is also the difficulty of attempting to reconcile an ‘internet’ tone of voice that may differ significantly from your own. Online, the lexicon mutates rapidly to suit the young audiences who engage with it most actively. In attempting to mimic ‘internet-speak’ some brands are already beginning to sound like the same snarky, disinterested teenager.

Source: Twitter

Your audience has the paintbrush, be the canvas

But just because brands shouldn’t create memes, doesn’t mean they can’t participate in the culture. There is a better way to build engagement around your brand: provide your audience with open-source toolkits that allow your communities to generate content on your behalf.

This is already something that artists in the entertainment industry are capitalising on. (Previously) independent Soundcloud rapper Lil Nas X has just broken the record for longest-running Billboard No. 1 single ever (19 weeks and counting) with a country/trap hybrid track built off a beat purchased from a Dutch teenager for $30. Dig deeper and you’ll find the catalyst for Old Town Road’s rise actually began last year with its use within a meme on the Gen-Z video sharing platform TikTok. On the platform, a mind-boggling three million videos were created using the track as part of a Harlem Shake-esque ‘Yee-Haw challenge’.

The success of this tune is no accident. It came because it was purpose-built to be exploited in the context of meme culture, whereby art is subverted and recreated by the end-consumer to fit their needs, not yours.

This way of thinking is crucial to understanding how to manage brands online. When you allow audiences to construct meaning in their own language it is much more powerful than trying to define it exclusively on your terms. Brands mean different things to different people, and by embracing polysemy you can magnify your influence far beyond what you could accomplish on your own.

Source: Facebook

It's time brands started tapping more consciously into their audiences’ desire for creation. It can be as simple as providing them a single, solid image to latch onto and carry over into their world. By repeating a consistent message, in a consistent tone of voice, you are already creating a cultural reference point that acts as a canvas for your audience to paint their art on. Nike’s ‘Believe’ campaign, Industry Superfunds ‘Compare the pair’ ads, and even the great Bunnings sausage sizzle are all fantastic examples of how memetic behaviour can be incited through repetition of a common theme (yes, memes exist of all three).

To take it even further, you could begin to release specific assets, or even certain elements of your branding system up for your audiences to play around with – setting the perimeters of the sandbox and allowing them to run free within it.

US Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg recently released an entirely opensource design kit to help followers support his grassroots campaign. In allowing even design newbies to create their own unique campaign assets, it embraces the idea of ‘adaptable relatability’, acknowledging the multitude of reasons an individual may gravitate to a particular candidate. Contrary to the largely controlled and static world of political branding, it’s an inclusive and unconventional approach that plays well with Pete’s complex and multi-faceted story (he is, among other things, gay, a military veteran, a Harvard graduate, millennial – and a devout Christian).

A final note

For brands, the difficulty in this approach is as much philosophical as operational. Co-creation in this manner is an admission that the boundaries of your brand belong to your audience, not yourself – and it’s a trust-fall exercise into the maelstrom that is internet culture.

But it’s also time to quit pretending the lunacy of the internet exists on some completely separate plane to the business world. The battle has already been decided, and for better or worse, this is the language of the online world - so don’t make the mistake of thinking your industry is too old-fashioned to be excluded from it. Rest assured, if it exists, you can meme it. Why not be in on the joke?